Culture and Daily life on Timor – A taste to tempt you

Religion and tradition

Christianity was the chosen religion in West Timor and Catholicism in East Timor, and despite the relative poverty in rural Timor, Sunday mornings are a bright and lively affair when people make their way to and from the churches on foot or truck dressed in their finest. I am usually the most crumpled grotty one on the bus.

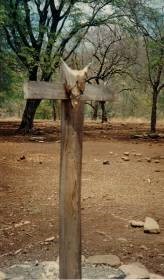

However, I find that Christianity is but a thin veneer as most of rural Timor still practice Animism, the worship of nature, honouring the elements and spirits of water, rocks, animals, fellow man, indeed all the things that enable us to live on this amazing planet. To this end Timorese weavings, statues and masks displaying cultural totems still have their role to play in Timorese society today.

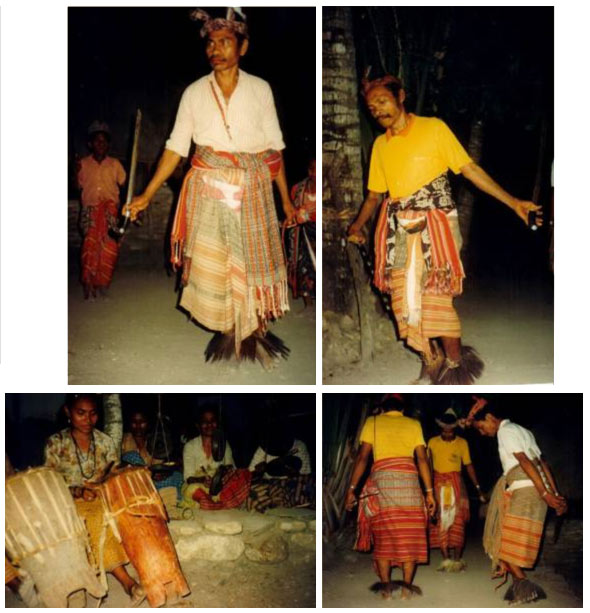

Dancing, singing, costume and musical ceremony (using gongs and drums) are all used to celebrate or ask for help from the ancestors. Some of the occasions that call for these ceremonies are: dowry exchanges, planting and harvesting of crops, divining of water sources, asking for prosperity, good health and weather, the offering of betel nut, the spinning of cotton, for the smooth running of village or regional affairs, for weddings and other celebrations; as well as offerings of friendship and reaffirmation of allegiance through loyalties or tribute. Interestingly men dance certain rituals and the women play the music.

Strong ties and allegiances still weave their way through Timorese society. Although the government puts its people into positions of administration and heading up the enclaves there is always a “popular ruler” and many of the traditional village roles are still active. For instance, there are medicine men, DUKUN and a DUSUN who [with the right offerings] may be able to advise you who may have taken your cow, crops or cash, or who cast a ‘sickness» over you; then advise what to do [often involving more offerings].

For an in-depth analysis of a section of rural Timorese social structures and culture please refer to “Paths of Origin, Gates of Life: a study of place and precedence in West Timor” by Andrew McWilliam. ISBN 9067181986. McWilliam’s bibliography includes other texts rich in information about Timorese customs and traditions.

Adverse changes in Timor

Some recent events have affected slow moving rural life in Timor. In 1998 the Indonesian rupiah fell to one third of its previous value, the price of rice trebled and wages didn’t. This deeply affected the poorer Timorese and is evidenced by the threadbare clothing seen in the kampongs. Food comes first.

The independence of East Timor in 1999 has put further pressures on West Timor, with a large influx of pro-Indonesian and displaced people requiring a place and plot of land. This is naturally followed by the need for extra water and wood for day-to-day living. Mostly the integration has been harmonious, but in some places closer to Kupang there has been violence and retribution.

A cooperative way of life

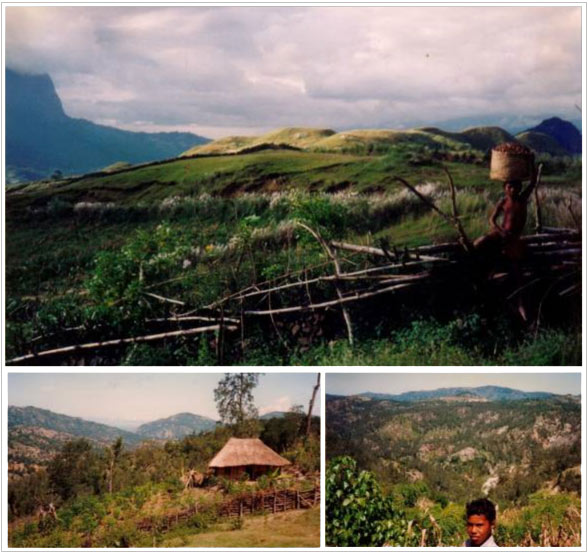

A cooperative way of life in the villages sees family groups working their gardens that are often two to five kilometres from the house.

You will also see groups of men singing and chanting as they make their way through the village carrying bundles of dried grass, handmade roof trusses and framework for walls and roofs of new houses. Building, repair and re-thatching of roofs require that the receiver or family must cater for the workers by providing a pig and food, drinks, cigarettes and ample betel nut to see the project through in good spirit. This can be a heavy financial burden, but a socially beneficial and bonding event.

Households that may have a waged job are opting for galvanised roofs instead. These are hotter in summer, colder in winter and deafening in the rain – but they take just one day to erect and may not need replacing for up to ten years, compared to the grass thatch which needs repair from five years on and replacement every 20 years or so.

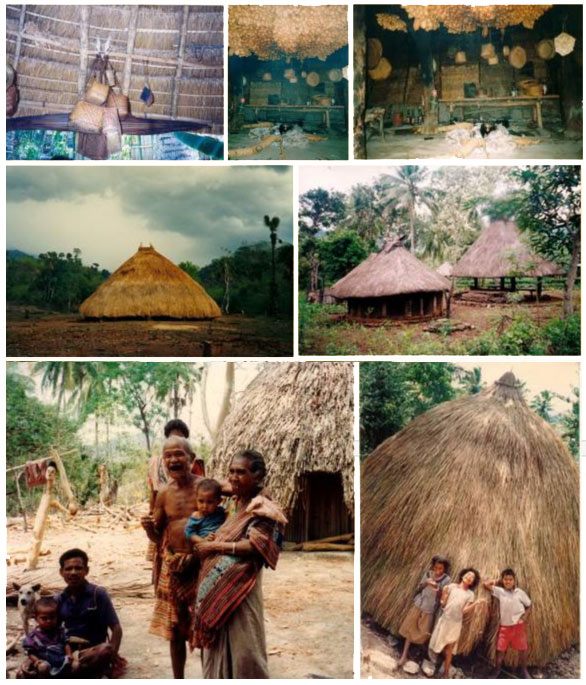

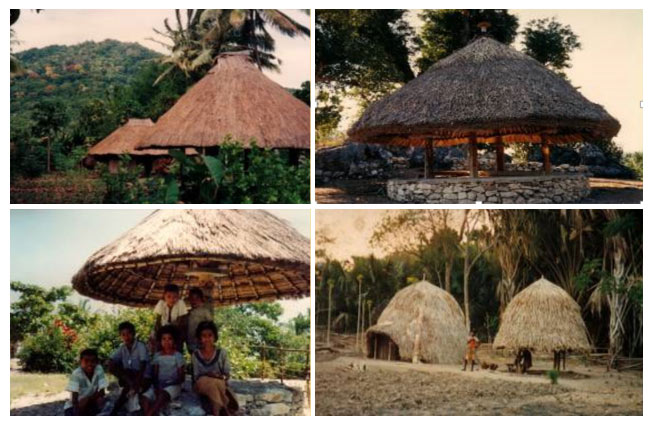

Timorese dwellings

Most Timorese have two or three dwellings on their land.

The first seen is the Lopo. This half beehive shaped grass thatch dome is supported by four large tree trunks or pillars that are capped by large disks of stone or wood to make the false roof rat proof. The floor is raised stone packed with mud. There are usually two platforms at thigh height between opposite pillars. These act as a resting place when it is hot; a place to weave and carve; or to sit and chat and chew. This is also a space to gather and dry the important corn crop, which will then be stored with the weavings and statues. It is eaten throughout the year as “pen bose” – corn stew – and the kept seeds are planted out in the next rainy season.

The main dwelling is a four-roomed square house – UME. At the front will be the “guest” or “greeting” room, usually containing plastic chairs and a small table for the serving of refreshments usually with a bedroom off that which usually contains a wood slat bed and grass mat, or if affordable, a kapok mattress (innerspring beds are for the well-off), and a small cupboard to hold personal effects. The back half of the house will usually have another bedroom, and there is a sort of dining tea and coffee preparation area.

The walls are often made of half handmade concrete blocks or rocks and the top half palm stems. The floors are all of compacted mud.

The Kitchen

The cooking, however, is done out the back in the “ume kububu“, the third dwelling. This is a large beehive with thatch to the ground, very thick and providing excellent insulation. The inside of the thatch is blackened with the smoke of countless cooking fires. There is rarely adequate, if any, ventilation, other than the small entry door. These are especially used in the “wet” season when pathways directly around the house turn to slush and the surrounding grounds, having been ‘opened’ at the end of the dry are worked as gardens. The success of the gardens in the “wet” dictate the eating and trading wealth of the family in the “dry” season.

The ume kububu has knee high bamboo slat bed frames around the back wall and often a homemade shelf for cooking utensils. From the cross beams hangs an assortment of household items, palm umbrellas, rice winnowing trays, hurricane lanterns, and skeins of cotton, often hanging off a boar’s jaw. Cooking is done on some strategically placed rocks and fed by wood in the centre of the room. Corn pounders stand alongside the handmade clay water pots. In a good season the inside may be lined with extra corn unable to be stored in the lopo, or for extra security.