Timor hand crafted carving and betel nut tradition

Lack of modern equipment such as cameras is one of the reasons the ancestral figure work is still present. As a means of honouring the departed a statue would be carved and usually kept in the false roof of the lopo. It is brought out to re-tell stories and remember. Similarly, guardian spirits, ancestor figures or totemic spirits are captured in wood for posterity.

The tradition of carving has been continued and is practiced by males exclusively. I have met one lady who carved fossil coral statues whilst her son and husband focused on other forms.

Regrettably the carving tradition that is still alive on Timor today has never really been written about nor documented. I have a photographic collection of all the carved items that I have traded over the last 30 years and I still have boxes that I have not opened.

There are approximately 40 carvers located in TTS. Virtually no one carves in Kupang or Belu regions. There are a few weavers holding the flame south of Kupang. The carvers work with whatever mediums are at hand such as wood (teak, red cedarwood, eucalyptus and palmwood), bamboo, coconut shell, gourds, bone and fossilised coral.

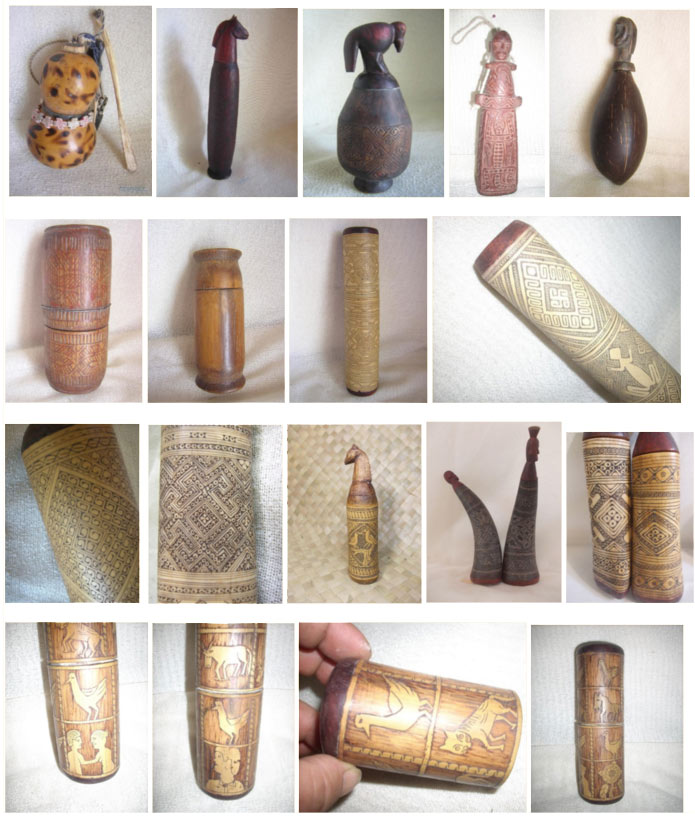

The betel nut ritual and accompanying paraphernalia

Pua or betel nut plays a significant role in Timorese society. Most men and some women enjoy a chew, some from early morning through to dark. It puts more oxygen into the blood and staves off hunger, allowing the people to work longer and harder. Much like the coca leaf for the South American Indians.

Where possible, the fresh nut is preferred, though dried betel is available all year. There is an asparagus type fruit thrown in the mix, and when this is not available the leaf of its vine will suffice. Add to this just the right amount of lime powder, and chew and chew, without swallowing.

Your mouth, lips and teeth turn red and you dribble as your saliva glands are activated, eventually spitting out the excess. Tossing in a wad of chewing tobacco is an optional extra.

Tempat Kapur or Lime containers are still made and used daily by the people of Timor. There is a distinctive style to house the nut, leaf and tobacco which is usually plain and another in which the lime powder resides, invariably intricately scrimshaw carved with the traditional motifs of Timor. Each one is unique and tells its own story.

Indeed since 2010 I have been witnessing an evolution in Timorese Betel Nut / Lime Powder containers. The story book KAL AU has been slowly creeping into some of the betel nut container makers treasures. From simple frog or crocodile motif cleverly worked between traditional diamond lozenge motifs I am now seeing full blown stories depicting many things from the phantasmagorical to modern mobile phone conversations. I have yet to document some of the more recent story book containers.

They are mostly made from bamboo although may be found in finely carved wood, gourds, bone, buffalo horn coconut even small sections of pvc pipes. Sitting beneath the tree in the heat of the day is a good time for a chew and to work on your latest container.

Much ritual surrounds the chewing of betel, and you can get a long way in Timor with your pockets full of betel nut.

It is a humble artform in which you will find Timorese art at its most unaffected.

Timorese statues and statuettes or ancestral guardian figures and totem poles

Timorese statues have a longer documented history, mainly due to the practice of recording ancestors and guardian spirits for posterity.

I do not know many Timorese who own a camera, let alone having the money to develop a film. Granted Smart phones have changed that for some. Statues therefore play an important role in storytelling and recalling passed members of the clan around the light of a candle with the kids in the evening. Such figures are usually kept in the false roof of the hut.

Sadly, many original figures have been acquired by unscrupulous dealers who do “raids” on distant kampongs and homesteads. The ploy goes like this:

Flash car pulls up to grass thatch hut. If no-one is home the pickings are easy as very few rural homes or false roofs in the beehive shaped huts are locked. Such dealers would help themselves and a few rupiah are tossed onto a table. If someone is in, the dealer will often force their way into the private storage place and remove the figures, asking what religion the people are. Not knowing who these people are and thinking they may get into trouble with the government if they confess to still being Animists, the people reply, “Christian”. “Ahh”, says the dealer, “then you don’t use or need this pagan object of worship”. Toss the person a pittance and make off with an ANTIK.

Fortunately, the tradition has continued and I am able to obtain a wide variety of treasures which I present to you.

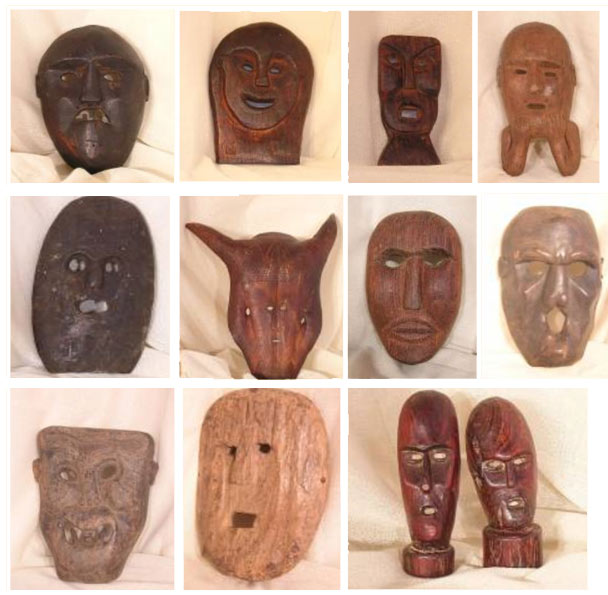

Timorese masks and maskettes

Timorese masks have a debated history. It is said the mask carving tradition began in the 1930s to cater for a meagre tourist trade and that prior to that mask making in Timor did not exist. I am neither able to confirm nor deny these claims.

The Timorese people that I asked say that the masks were traditionally carved with “ugly or scary” faces and placed inside the hut, above the front door; so that people of bad or evil intent could not pass beneath, whereas those of good heart and intent would have no difficulty. Kind of like a Star Trek force field.

Masks with paddle handles are used in ceremonial dance. Their secondary purpose is to provide anonymity to the wearer when in times of food shortages, it is deemed acceptable to put on your “mask face” and sneak over to the neighbours and steal food. Likewise, you may find your “faceless” neighbour doing the same a short time later.

I find this amusing as no two pieces of Timorese handcraft are the same and indeed many are signature pieces of their creator therefore anonymity is actually quite impossible. But I understand the concept.

And as my field collecting companion Aja from Canada says “and then there are those that find you”.

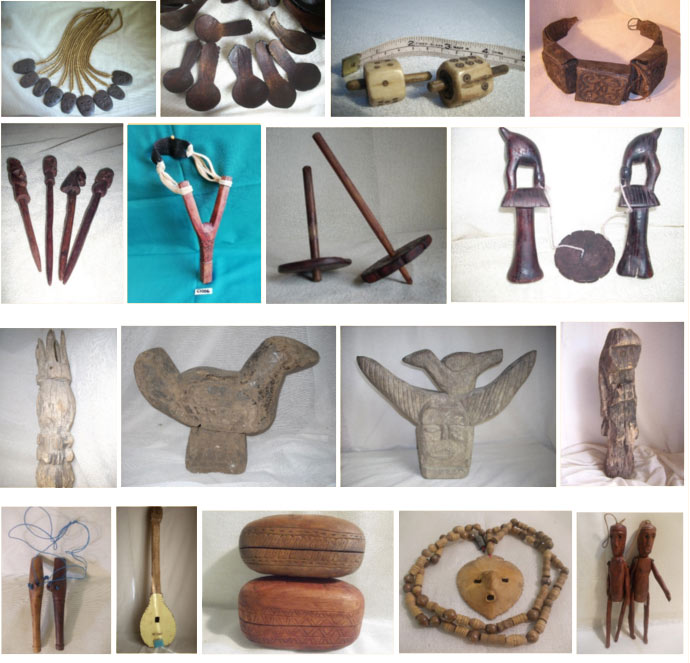

Examples of curios within the carved crafts of Timor

Examples of the curios are walking sticks, catapults, cotton gins, drop spindles and parts for the weaving loom. Toys are as simple as an amazing variety of spinning things from spin tops to disks on string and, string pulled propeller type in all sorts of shapes. Oware/mancala games and dice made from many mediums such as wood, bamboo deer horn even plastic. Puppets are a favourite with the kids and adults consider them fetish symbols.

Other examples are jewellery such as bracelets, head combs and hair pins, necklaces and rings; large bamboo “lunch boxes”, coconut shell and wooden spoons, even roof gods or finials, totem poles, doors, seats, beds and musical instruments such as guitars, violins, drums, gongs, flutes, juice harps and recorders.

All hand fashioned using the simplest of tools.

Betel nut and lime powder containers are in a class of their own so broad is the variety of medium that the Timorese use to make them with.

Timorese Pottery

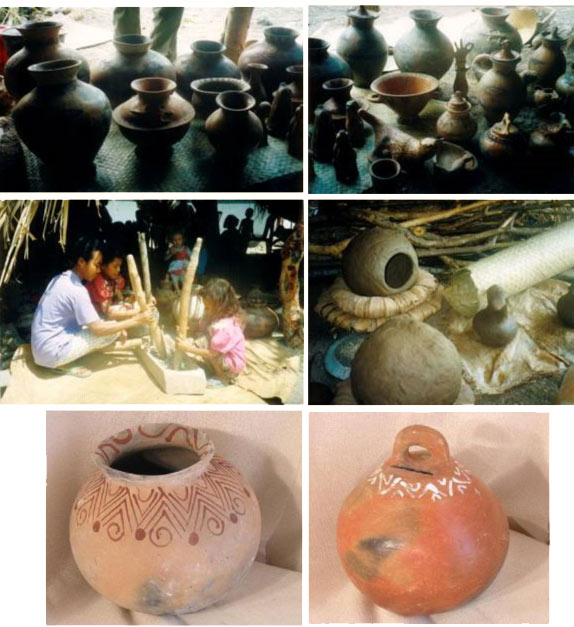

Timorese pottery also has its own distinctive style. There are potters in most provinces, predominately women serving local needs. Pots are made mostly for carrying water from the well or river which can be up to 2 km away. Some are made as medicine and herb cookers and storage. Most pottery is low fired in a stack with a timber tepee around it.

The same NGO who assisted with the Lombok pottery project also helped create one in Timor. Sadly the project was placed too far from transport to be viable, especially as the group encouraged the making of large vase urns dramatically changing the style of pots that Timor traditionally makes and provided no sustainable solutions for packing and transportation to markets, domestic or international for the pots. It therefore died in the same way I have watched so many culturally and geographically inappropriate aid or assistance projects go in Timor.

All handcraft is distinctly Timorese

Still today, with virtually no outside influences betel nut containers, statues, masks, textiles and indeed all Timorese handcraft, is quite distinctly Timorese. Across a period of 3 decades, I have witnessed their crafts evolve. Some similarities may be drawn with Papua New Guinean statues and even Nepalese masks. I believe this to be more of a collective consciousness thing, kind of generic. You can be assured that the craft comes purely from the carver’s hearts and imaginations. Each carving and weaving is unique.

I am careful not to influence the crafts that the Timorese create. I collaborate with a “tread carefully and watch what you leave behind” approach. I have seen the results of a few handcraft projects that have been instigated through well intentioned NGO’s in Timor, projects which rarely benefit the culture or crafts people.

I trust that you will enjoy with me the pleasure of these Timorese Treasures.

© Julie Emery / Timor Treasures 2022

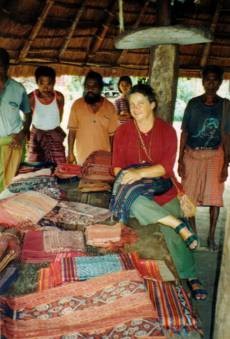

Post-independence referendum in the streets of Dili 2000 I met some carvers from Atauro. Sadly, most have lost their traditional totems and are copying imagery from the Chinese shops in town. The joyful fellows with the cart are catering to the UNESCO workers who take tais home as souviners. Although little understood by the workers they are helping to keep a cultural tradition alive.